We would like to summarize the history of whetstones as explained by Professor Fujiwara on YouTube.

Since we are discussing history, we should not take this information as 100% factual. Instead, we would like you to enjoy it with the mindset that these are the potential backgrounds and ideas of the time.

Conversely, if we have any questions or new thoughts, such as “Could it be this way instead?”, we should feel free to leave a comment!

Whetstones are the foundation of everything

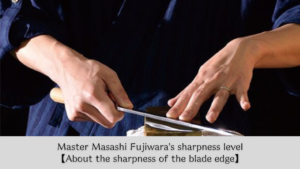

We believe that whetstones are the most important element when discussing knives and their sharpness, as Professor Fujiwara suggests.

While the shape of the knife and the type of steel are certainly important, we can say that the whetstone serves as the foundation for everything.

That is exactly why Professor Fujiwara develops his own whetstones, and we think this highlights their true importance.

Kensho whetstone | Tsukiyama Yoshitaka Hamonoten

We believe that the whetstones provided by Professor Fujiwara are the best in Japan. This is because they are the only ones in the country who inspect every single whetstone before selling them, and their level of expertise is unlike anything we have seen elsewhere.

Now, let we take a look at the history of whetstones.

Ground Stone Tool Age: A turning point in processing technology

The Ground Stone Tool Age in Japan corresponds to the Jomon period, which began about 14,000 years ago. People started to live in permanent settlements and began cultivating plants in addition to hunting and gathering.

As the tools for daily life became more diverse, we saw a major turning point in human processing technology: the shift from “chipped stone tools,” made simply by striking and breaking stones, to “ground stone tools,” created by rubbing stones to shape them. At this point, we moved beyond the stage of just “breaking” and established techniques for shaping, such as “honing” and “polishing.”

The act of rubbing stones together to achieve a desired shape can be called the origin of “sharpening” that continues to this day. In fact, since wear marks are found on stone tools excavated from ruins of that era, we assume that a concept similar to “whetstones” for polishing stones already existed and was being utilized.

Whetstones are tools that continue to play an important role even today in terms of “making things.” We may have few opportunities to think deeply about whetstones in our daily lives, but it is undoubtedly the “whetstone” and the technology of “sharpening” that have had an extremely significant impact on human civilization. We can say that the whetstone is by no means just an accessory to a blade, but was the starting point that supported the very culture of human processing.

Yayoi Period: The “Distribution” and “Selection” of Resources

The Yayoi period lasted for about 1,300 years, from around the 10th century BC to the middle of the 3rd century AD. During this time, the social structure shifted significantly from a lifestyle centered on hunting and gathering to full-scale rice cultivation, which created a massive demand for ground stone tools for woodworking.

In this era, whetstones were no longer just common rocks; they became an important resource transported from specific production areas. Analysis of whetstones excavated from ruins shows examples of stone types that do not exist naturally in those local areas. This suggests that a distribution network had already been established to procure “high-quality stones” from afar and transport them to where they were needed.

Even back then, there may have been individuals like Professor Fujiwara who could distinguish between a regular stone and a proper whetstone. While it is thought that various types of stones ranging from coarse to medium grit were available since the age of ground stone tools, it is believed that they began to be selected more strictly based on their performance as tools—for example, “how quickly they could grind.”

Since securing such high-quality whetstones directly impacted a village’s productivity, having a discerning eye for the properties of stone and a network to obtain them stably played an extremely vital role in the society of that time.

Heian Period: The Hierarchy of Quality and the Birth of “Names”

The Heian period lasted for about 400 years, from the relocation of the capital in 794 to the end of the 12th century. While aristocratic culture flourished, this era also saw the rise of the samurai class and the widespread use of iron tools, leading to a refinement in both technology and aesthetics.

During this time, whetstones began to be referred to by specific names, and a clear hierarchy based on quality emerged. A primary example is “Iyodo,” which was quarried in what is now Ehime Prefecture. Records showing that Iyodo was transported all the way to the capital indicate that differences in whetstone quality were already widely recognized.

It was an era where the value system for tools matured, establishing that a “good stone” was worth the effort of transporting from afar. As common rocks became recognized specifically as whetstones—and as quality differences became distinct—names were created for identification, and value was assigned to the stones.

While it is assumed that coarse and medium stones focused on work efficiency were the mainstays until then, the existence of manufacturing technology for ironware in this era suggests that people were already able to seek sharper edges and the finer stones required to achieve them.

Kamakura Period: Finishing Whetstones and the Japanese Sword

The Kamakura period lasted from the establishment of the shogunate around 1185 until 1333, an era where the samurai became the protagonists of politics and might made right. With the major shift from an aristocratic society to a warrior society where the samurai held real power, the military industry came to play a central role in the nation.

During this era, many high-quality natural finishing stones were discovered in the mountains of Kyoto, and they were treated as precious resources, even presented as gifts to the Emperor. At the time, the discovery of whetstones capable of bringing out overwhelming sharpness dramatically improved lethality in battle, making them military tools that could sway the outcome of a war. Because that power could sometimes become a threat, it is said that whetstones were strictly controlled. It is also possible that the shogunate managed advanced technology by employing exclusive blacksmiths.

Furthermore, it was during this period that a sense of “beauty” was established alongside the pursuit of sharpness. While natural medium stones produce a finish where the surface looks white and hazy, the use of natural finishing stones began to create a brilliance never seen before. This allowed the unique patterns of Japanese swords to emerge clearly, opening up a world of beauty that transcended performance as a tool.

The existence of superior whetstones pushed the boundaries of sharpening technology, and that heightened technology, in turn, spurred the evolution of tools. While it is unclear which came first, it was precisely because of these excellent natural whetstones that the dramatic evolution continuing to the present day was achieved. Globally speaking, the production of natural stones with such a rich variety of hardness and softness is almost limited to Japan. This can truly be called a miraculous environment that symbolizes Japan’s sharpening culture.

As a side note, there may be a reality slightly different from the image we have today regarding how blades developed with such technology were actually handled on the battlefield. In fact, the mainstays of battle were not swords, but weapons like bows and arrows, spears, and in later eras, firearms. On the battlefield, range and length are most important; when fighting in groups, it is overwhelmingly advantageous to shoot with bows or guns from a distance or to strike and thrust with long spears rather than charging in with short weapons like swords.

Looking at records and picture scrolls from that time, there are many depictions of footsoldiers (ashigaru) creating walls with spears or throwing stones. The idea of a lone warrior swinging a sword and taking on a thousand enemies is likely heavily influenced by later fictions and stories. So, what was the sword? It is presumed to have played a role like a handgun does today—a sub-weapon. It was used as a last resort when a spear broke, arrows ran out, or during a grapple with an enemy. It also played a large role as a tool for finally cutting off the head of a defeated enemy.

The fact that so many Japanese swords remain without a single scratch allows us to speculate that modern Japanese swords differ from military weapons. Practical swords from eras like the Sengoku period were consumables where sturdiness and sharpness were prioritized over artistic beauty. Many were mass-produced and handled as if they were disposable. It can be predicted that the beautifully refined Japanese swords we see in museums today were custom-made items or offerings held by high-ranking generals, made after the spiritual significance became stronger, and were somewhat different in nature from the gritty weapons used in actual combat at the time.

Edo Period: The Era of Peace and the Spirit of “Mottainai”

Regarding “Mottainai” The Japanese word “Mottainai” reflects a spirit of respect for objects and a sense of regret when something’s intrinsic value is wasted. It encompasses the ideas of “Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle” along with a deep gratitude toward resources.

The Edo period was a long era of peace that lasted for about 260 years from 1603, during which the Tokugawa shogunate ruled Japan. Under the policy of national isolation, a unique culture flourished, and with the improvement of roads and the development of commerce, the standard of living for commoners in urban areas improved significantly.

As society stabilized during the Edo period, woodworking tools and kitchen knives for cooking finally became deeply rooted in the lives of common people. The Hon’ami family, who served as the official whetstone providers for the shogunate, was entrusted with the management of natural whetstones. A supply system for whetstones was established as high-quality stones began to be distributed to the privileged class, while others reached the general public.

Since resources were limited at the time, the spirit of “Mottainai” was strong, and the culture of sharpening and repairing tools to use them for a long time became established as a social infrastructure. Tools were no longer just consumables; they transformed into “partners” that one would stay with for a lifetime through repeated maintenance.

In the field of food, it is said that techniques such as “pull the Yanagiba to cut” and “do not move it back and forth” had already spread to the general public by this time, suggesting the development of a rich culinary culture. It can be considered an era where the stability of a society without major wars nurtured a mindset of spending time and effort on a single tool, as well as the meticulous dedication of both craftsmen and commoners.

Meiji to Early Showa Period: Modernization and the Birth of Synthetic Whetstones

The period from the Meiji era to the early Showa era spans from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 to around World War II in the 1940s. It was a turbulent time when the era of the samurai came to an end, and Western mechanical technology and industrial products flowed in with the “Civilization and Enlightenment,” leading to Japan’s rapid growth into a modern state.

During this era, while the quarrying of natural whetstones reached its peak, synthetic whetstone technology emerged. Abrasives were born in the United States in the 1890s, and by the 1940s, it became possible to create whetstones artificially. The shift from natural whetstones, where high-quality items could not be obtained consistently, to synthetic whetstones, which could be produced uniformly and stably, was a major evolution.

However, behind this shift, it is said that natural whetstones, which required specific knowledge to master, were avoided, and some were even thrown away under the belief that “if there are synthetic ones, natural ones are unnecessary.” It was an era where the traditional skills of craftsmen and modern industrialization, which prioritized efficiency, clashed intensely, causing the values surrounding tools to be shaken to their core.

Showa Late Period to Heisei: The Reversal Phenomenon of Steel and Whetstones

The late Showa to Heisei period, spanning from the high economic growth of the 1950s through the 2019 era, was a time when society matured as it leaped from post-war reconstruction to becoming an economic superpower, and mass production and mass consumption became the norm.

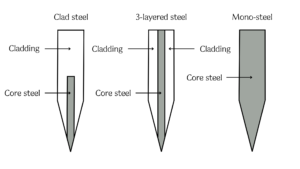

With the widespread use of synthetic whetstones, sharpening transformed from being based on a craftsman’s intuition into a reproducible technology. While it was difficult to fully sharpen hard steel with natural whetstones, the evolution of synthetic whetstones made it possible to grind even harder materials. It is a fact that certain steel types only began to receive proper evaluation during this era because of this.

In the past, blacksmiths created tools to match the existing whetstones, but because precise mechanical manufacturing is now possible, there is an aspect where performance is completed solely by the knife itself. In this environment, it has become an era where it is harder for the user’s voice to be heard, and the culture of repairing one’s own tools has simultaneously faded.

Amidst these trends, the appearance of diamond whetstones was a revolution for environments seeking the ultimate sharpness. Particularly as a tool for flattening, they made it possible to accurately correct the distortion of a whetstone in a short time, a task that previously required significant time and effort. By making it easy to maintain the flat surface of the base whetstone, the precision in bringing out the sharpness of blades improved remarkably.

While disposable items increased in the world, for the handful of people pushing technology to its limits, it was an era of dramatic evolution. It could be said that it was a time when the gap between the general public and specialists widened significantly.

Finally: An Era of Many Choices

In the past, due partly to environmental factors where people had no choice but to value and use items for a long time, it was natural to maintain tools oneself. However, in the modern era, inexpensive and high-quality items are mass-produced, and there is a tendency to prefer products with a more instantaneous impact.

As technological improvements have made it easy to obtain items of a certain quality, we have entered an age where there is no particular trouble as long as decent things are made in a decent manner. The advanced technological development of today has already far exceeded the purpose of mere survival. For this reason, in a world where delicious things rated at 70 points can be easily created, the reality is that almost no one remains who pushes themselves to reach the level of 95 or 96 points.

However, precisely because it is such a peaceful and fulfilling era, perhaps there is value in a “world of pursuit”—where at first glance the meaning may be unclear—showing us something new. Now that technology has developed and we should be able to choose from more options, I believe it is a great shame to stop at the “decently correct answer” that everyone else chooses.

Today, both natural and synthetic whetstones are at an extremely high level, making this the era in history where one can most pursue sharpness. Being able to choose your tools means being able to choose the very taste of your cooking. If the culture of sharpening spreads once more and we cherish this “miracle” of investing time and effort, it should lead to a richer future culture.